After deliberating over the purchase for a few years, my latest set of reference books arrived recently, so I thought I’d write a bit about curating a home reference library.

Actual reference books have been an endangered species at least since I was directed to an Encarta CD-ROM in my high school library in 1996, and I’m not opposed to googling things as needed, but I prefer to start with some sort of paper-based reference material for questions like “how do cameras work?” or “where is Mongolia?” Books lend themselves to browsing serendipity while asking Siri does not. Furthermore, the children are free to use any of our books at any time independently, whereas they require my assistance and/or supervision to make use of the internet.

What counts as a reference book as opposed to any other sort of book? In my mind, these are the sorts of books you wouldn’t tend to read straight through and that you read for the sake of some other extrinsic purpose, not just for the sheer enjoyment of the reading experience itself.

Still, even instrumental reading can be more or less appealing, and the more appealing the material, the more likely one is to find themselves reading on about the re-discovery of Machu Picchu, even if you started out just wanting to know the population of Peru. I try to select books that invite this sort of browsing, whether through attractive illustrations or compelling authorial voice (often hard to come by in reference works).

I tend to think of reference books as falling into two broad categories: one type of book you turn to in order to know something and the other in order to do something.

Things to Know

If I had to pick just one set of reference books, hands down it would be a vintage World Book encyclopedia. We had one from the 60s when I was growing up, and I browsed it A LOT. My kids use these multiple times a week; they are pretty much always spread out all over the floor, often with two different volumes open to related articles left next to each other. Our set is from the 80s - I cannot speak to how the presentation may have changed in more recent years.

We have a copy of the second version of a 15th edition Britannica, too, and I also like it, but it doesn’t entice you to browse in the same way. I actually think the micro/macropedia arrangement is neat, though, and the more in-depth information is good for older kids who have already been reading the World Book for a few years.

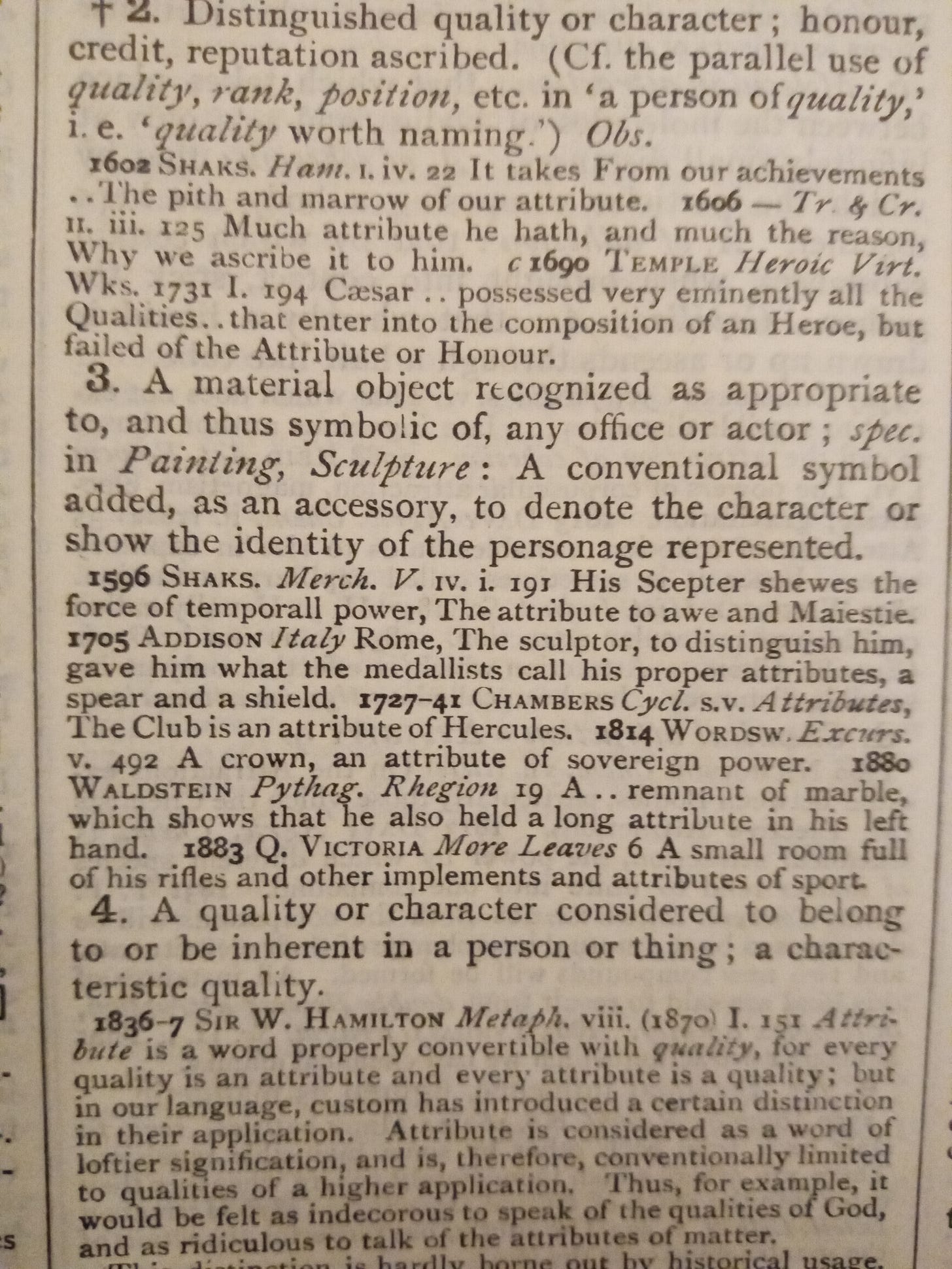

I remember clearly the day I noticed the set of very thick books high on a shelf at the used book store run by our local Friends of the Library - could it be an Oxford English Dictionary? It was! For a mere $125! I’d coveted a set since high school, when my extremely cultured English teacher had told us it was the only dictionary worth consulting.

To be sure, it is a rare child who will pull one of these volumes off the shelf on their own initiative, but they have been invaluable in our homeschool, and I think the kids are starting to see the utility. At the very least, they all get a real kick out of it when we go to look up a word from something we are reading and discover, in the quotations, the very work we are looking at!

While most of our reference collection I’ve picked up used,1 I did buy a comprehensive atlas new so we would have one fairly up-to-date geographical resource. About a decade ago, the Principal collected all of Colin McEvedy’s historical atlases, and I recently added a fun baby’s first historical atlas by DK to introduce the younger kids to the concept. Also frequently browsed are Material World and Hungry Planet.

One good field guide for your region is probably a good idea, but I think only families with a real naturalist bent need more specialized volumes. Our collection is a random assortment of what I’ve picked up used over the years.

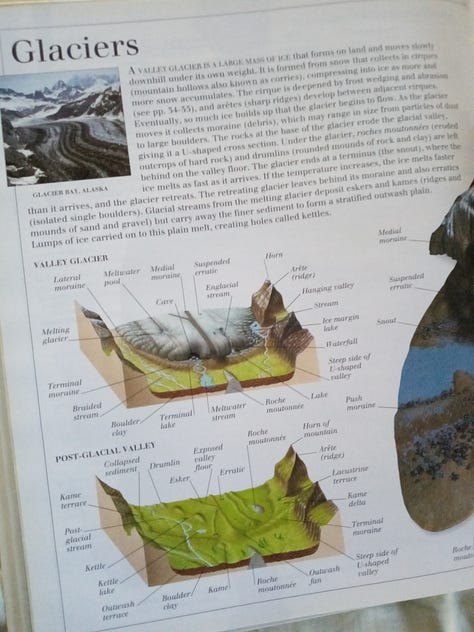

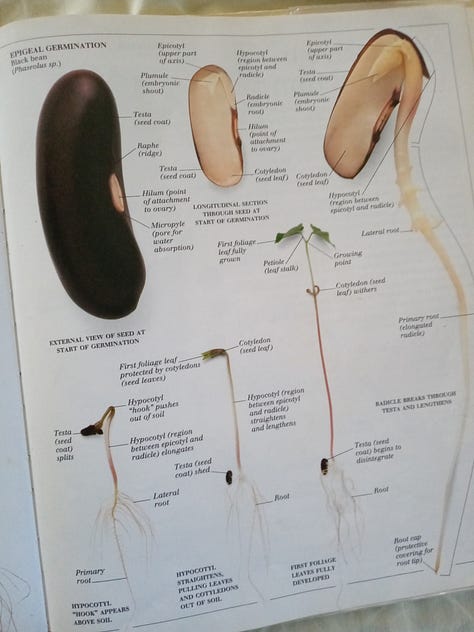

I try to keep DK and Usbourne books of the disconnected, factoid type to a minimum in our permanent collection (we do check them out from the library), but I have made space for a few of DK’s “visual dictionaries.”2 These are excellent to pull out as a visual supplement to any verbal description of pretty much anything - layers of the earth, parts of a plant, aircraft of World War I.3 I have some kids who have been inspired by these to make carefully labeled drawings of their own. Along similar lines, we also have an older edition of The Body Atlas.

As my kids are getting older, I’ve started collecting high school and introductory college textbooks covering a variety of disciplines. We haven’t made extensive use of any of these in our formal academic work, but I am finding them useful to have around to supplement our less-conventional high school content studies. It’s slow going, though, as I’m trying to poke around a bit and see which textbooks actual experienced instructors in these disciplines like to use and why.

If you do any foreign language study, I recommend having more than one good grammar to reference - sometimes a slightly different explanation of a grammatical concept can really make the difference. For Latin, we have Allan and Greenough and Gildersleeve. Benedict’s godmother gave him a hardback Lewis and Short for his birthday a couple of years ago, and I will have to replace it if he takes it away with him to college.

Finally, religious reference books: A Bible, duh. Or several, to compare translations. And a Vulgate, if you study any Latin at all. We also make regular use of a catechism and a copy of the Summa.4 ETA: I forgot our liturgical year reference books! And collections of lives of the saints!

Things to Do

I have a history of overbuying these sorts of books, and I’m here now to tell you what is actually worth having around: books that give good explanations of general techniques and books that provide a lot of inspiration, particularly visual.

Less used are books that just have narrow instructions for a handful of very specific projects - rarely do the projects in the book match up with the usually much more ambitious projects that exist in a child’s mind. At the very least, I would recommend previewing these sorts of books from the library before purchasing.5

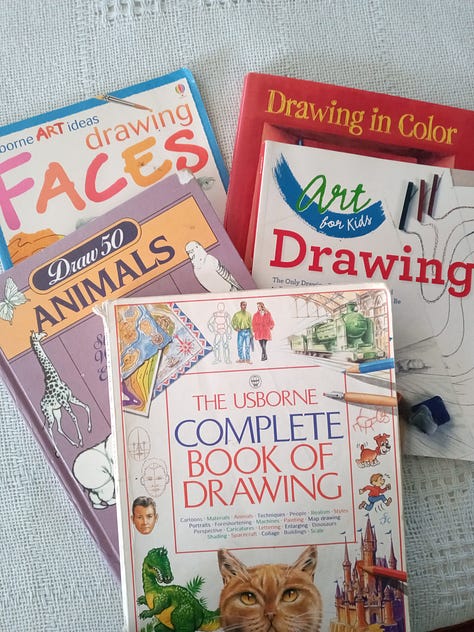

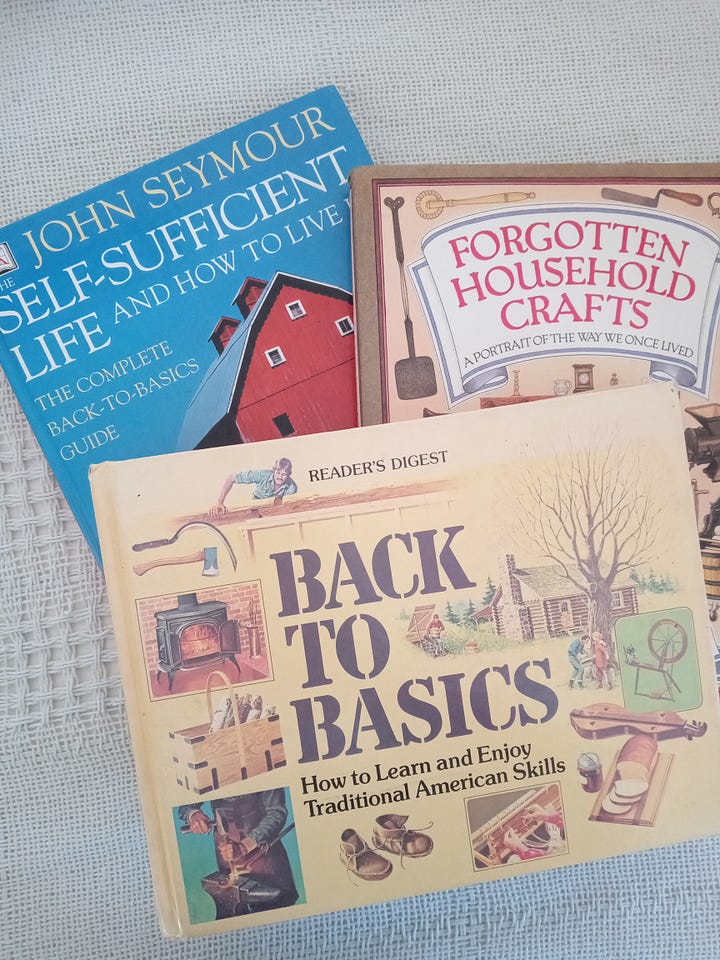

For techniques, we have many old Reader’s Digests volumes, which are cheap, quite comprehensive, and generally have good photos, although the actual projects in them are quite dated. We have a variety of drawing books, including some good general ones from Usbourne, several from Lee Ames’ Draw 50 X series, and a few by Ed Emberley that the Principal is very partial to.

For crafting inspiration, honestly the kids love Martha Stewart. In addition to the two craft encyclopedias we own, we often check her seasonally-themed books out from the library (Edmund is using a Halloween one to plan decorations for a bonfire, donuts, and spooky stories gathering next week). Also inspirational/aspirational if your family has a large-ish outdoor space are books written by Daniel C. Beard (a founder of the BSA) and his sisters; we own the American Boy’s and Girl’s Handy Books, the Field and Forest Handy Book, and The Book of Camp-Lore and Woodcraft.

You’ll perhaps have noted that there are no books of science experiments in our collection. I’m not a fan - these are almost universally books of disconnected projects that don’t always work well and don’t seem to serve any greater purpose but are easily marketed by slapping STEM! on the cover. I’m sure there are some decent ones out there, though - please let me know if you’ve found them!

How to get your kids to actually use your reference materials:

What specific

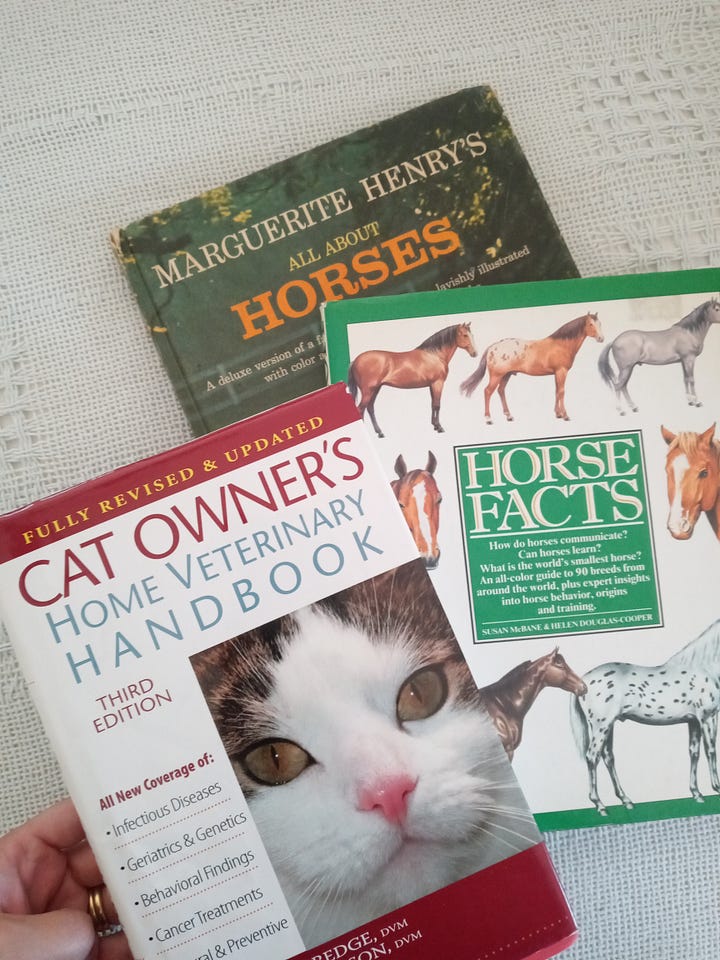

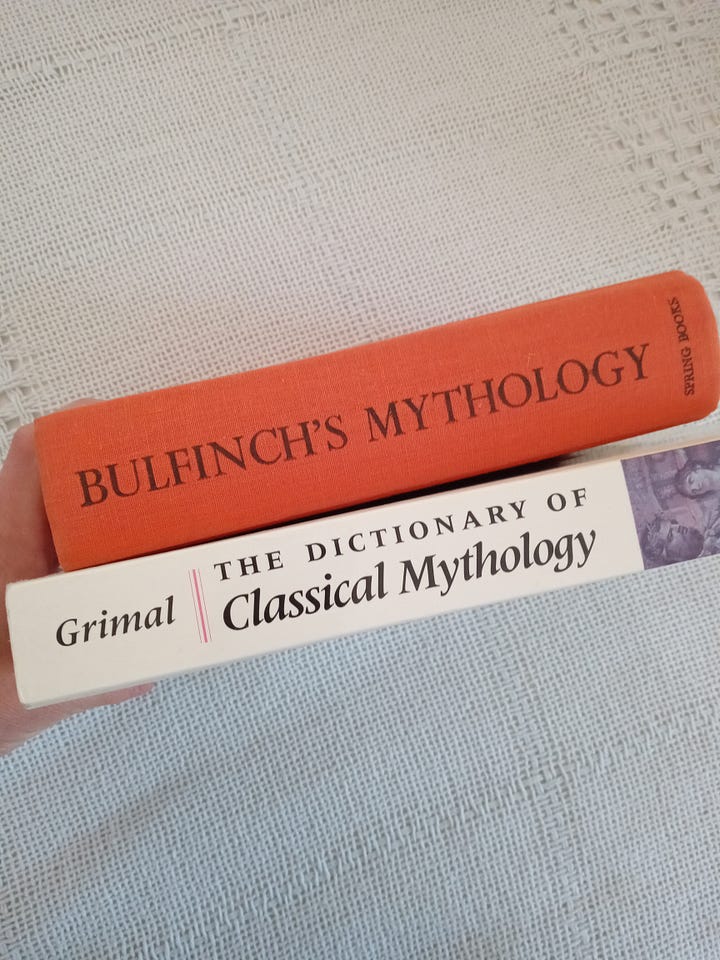

weirdunique thing might yourweirdunique kid ask about? Tailor your collection to the types of things your kids actually wonder about or want to do. For example:

Match the kid to the books! When a child asks you a question, unless it’s something you have a particular expertise in or unique perspective on, tell him to look it up. Yes, he will find this irritating at first, but also yes, he will get over it in time. Sometimes he will decide it’s not worth the effort and drop the whole thing - at this point, you must resist the impulse to answer the question for him after all! If he does investigate his question, make sure you ask him later about what he learned and find it deeply, engrossingly fascinating. And now you can feel free to add anything important he missed or point out a connection you’d like him to notice.

If he is too young to use the right book himself, ask him to bring you the book and have him stand next to you as you narrate aloud the process of finding the right entry in the book. “Let’s see, how do we spell Hereford? H-E-R, so I turn to the Hs, and I open it to, let’s see, ‘Holland.’ That’s spelled H-O-L. Does O come before or after E in the alphabet? Right, so I actually need to go back to the words that start with H-E. Okay, here are the H-E-Ts, I need to go back still further, aha, the H-E-Rs, hm, but there’s no entry for Hereford. That’s a type of cow, though, so what if you bring me the C volume and we look under the entry for cows or maybe it will be under cattle?” Eventually6 he realizes he can do all this much faster than you can and stops asking you for help.

Put the heavy books on low shelves that are easier for small people to access. This is prudent for structural bookshelf engineering reasons also, though I’m sure you’ve anchored your bookshelves to the wall, right?

Don’t freak out about multiple encyclopedia volumes being left out all the time, which they will be. Just calmly ask the responsible party to come back and reshelve the books properly.

Consult your reference works when you are reading aloud. Not sure what a doublet or a Spanish arcabucero is? Or where to find Flanders and why Miles Standish might have been there? Often the only thing between us and the actual enjoyment of some slightly older work of literature is just a little bit of background knowledge.

Require their use for formal academic purposes. Much of the academic work we do here in the “content subjects” for grades 4-8 involves students doing independent research with reference materials. The earlier editions of The Well-Trained Mind contained helpful guidance for this,7 though as time has worn on, I’ve tended to make more use of Montessori-ish research templates.

Let the kids see you using your reference books. I use many of the books in our family collection, but also have a few things that are more specific to me, like Home Comforts, a comprehensive book of knitting techniques, and many, many cookbooks.

At this point, we have a pretty good general reference collection, but I am always on the look out for volumes to fill gaps or address an individual child’s weird unique interest, so if there is a reference book in your home that is never where it should be on the shelf because it’s always in use, I’d love to hear about it!

You can find everything online, of course, but library book sales are also real goldmines, support your local library, and are just a good time.

It looks like many of these have now been published together in one enormous volume.

Also a gift from the aforementioned godmother - she is just an amazing gift-giver with the exception of the year she gave Benedict a set of tiny instruments for his 2nd birthday.

There are a some well-designed exceptions that use individual projects to gradually build skills, and if you have a kid who likes working straight through from the beginning of a book to the end, these can be a good fit. My one son like this worked through Electronics for Kids and had his room rigged up with an incredibly obnoxious alarm by the end. He also liked Rubber Band Engineer so much he wrote the author a fan letter (the guy wrote back! really nice dude).

“Eventually” can mean years, not weeks. Certainly at least months.

Maybe the current edition still does! I’ve heard it’s more a compendium of curricula recommendations, but have not looked at it myself.