Could John Stuart Mill Have Saved Our Schools? by Siegfried Engelmann and Douglas Carnine

Do you ever wonder why debates over education from the last century or so seem to eternally return to the same obviously false dichotomies? Student-centered or teacher-driven? Critical thinking or content knowledge? Relevant or timeless? Lecture or exploration? Telling or doing? It’s both, duh! Why do we have to keep having this conversation?

It’s because we don’t beat students any more.

As if that hadn’t already made classroom management hard enough for teachers, we also want everyone to learn more in school than ever before - much more. For a very very long time, the formal curriculum for students at the ages we now know as K-12 was nothing followed by Latin, Latin, and more Latin. Even if you want to count all the classical liberal arts - the famous trivium and quadrivium, which were not actually universally taught throughout the middle ages - you are up to seven subjects: grammar, logic, rhetoric, music, arithmetic, astronomy, and geometry.

Today, high school graduation in my state requires four years of English, four years of math (including algebra I and II on top of geometry), biology, chemistry, physics, computer science, history (US and world), civics, economics, personal finance, physical education, fine arts, and foreign language. Also three elective credits. And don’t forget all the ancillary aspects of K-12 education, from drivers ed to health class, those things designed to produce, as Jacques Barzun once wrote, "ideal citizens, supertolerant neighbors, agents of world peace, and happy family folk, at once sexually adept and flawless drivers of cars."

The problem is not everyone actually wants to learn all those things, at least not enough to put forth even minimal effort.1 The problem of mass education is the problem of motivation, or what used to be called docility, the degree to which one is able to be docere-ed, to be taught. St. Thomas says that docility is an essential cognitive habit for acquiring knowledge by teaching, but one that seems to be in short supply.2

I collect vintage school readers particularly those from the early 20th century, when the serious study of vernacular literature was beginning to take its place in the post-classical school curriculum. In very many of these readers, students encountered the fable of the blind men and the elephant - a varying number of blind men take hold of different parts of an elephant and then, each convinced they have grasped the whole of the creature, argue bitterly about its true nature.3

I know of no fable that better describes educational theorists in the age of mass education.

The arguments between progressives and traditionalists, with hands clamped firmly on tail or ear will never, ever end. Progressive educators often tackle the problem of motivation by way of adjusting the curriculum to the student - making the material to be studied actually or apparently more "relevant" to students lives, interests, and desires and/or giving students more autonomy to determine what they will study.4 E.D. Hirsch calls this the “sentimental absurdity that each child must have his or her own special curriculum suited to his or her special personality,” and, in addition to justifying the elective system in higher education, these ideas have doomed millions of K-12 students to frustrating group projects, depressing "issue novels,” and never internalizing their times tables. Among homeschoolers, you find radical unschoolers counting on baking enough triple-batches of cookies to produce proficiency in fractions.

Hirsch was right that the progressive approach, by denying students the opportunity to acquire cultural literacy, ultimately has undermined mass education’s own egalitarian goal “that schooling should enable every person to stand on his or her own two feet, equal to every other person of similar talent and virtue, rather than, as in the past, having one's role in life determined by the status, wealth, or education of one's parents.” But he himself has never been particularly interested in the pedagogical problem progressives try to address, leaving that to other educators - such as Siegfried “Zig” Englemann.

Engelmann was the progenitor of capital-D, capital-I Direct Instruction, an application of behaviorism to pedagogy and curriculum design.5 He retired as a professor of education at the University of Oregon but started his career in marketing - specifically, significantly, marketing to children - and while cognitive scientists moved on from behaviorism in the 1970s, Engelmann never did. Today, his organization, the National Institute for Direct Instruction publishes programs primarily for elementary math and language arts, including some that will be familiar to homeschoolers.

Engelmann declares at the outset that he is “not really concerned with unbounded ‘learning,’ but only with the type of learning that is caused by teaching.” His essential insight is that - contrary to the assumption behind every reading comprehension curriculum that has ever existed - making inferences is not a skill that students need to be taught, but that “children’s minds are wired to draw inferences.” This ability is “part of the data processing mechanism that children inherit.” Engelmann sidesteps the problem of interesting students in learning by arguing that learning is basically effortless and automatic because human minds are inference-making machines. Education, it turns out, does not have to require much demotivating mental toil - at least on the part of the student.

Here is the catch: students will always make inferences “consistent with the example sets” they are presented with; in fact, they cannot do otherwise, any more than you, a fluent reader, can decline to read any text that enters your field of vision. Ambiguous examples are what add friction and confusion to the learning process; “if the examples presented generate more than one meaning, not all learners will learn the same thing.” The job of the curriculum designer (not, Engelmann is clear, the teacher) is to undertake a meticulous analysis of the material to be taught, breaking down the content into the smallest possible inferential jumps, placed in the most logical sequence - which may or may not correspond to how the discipline has traditionally been taught - and then to assemble “example sets that generate only a single inference” to lead the student through the material.6

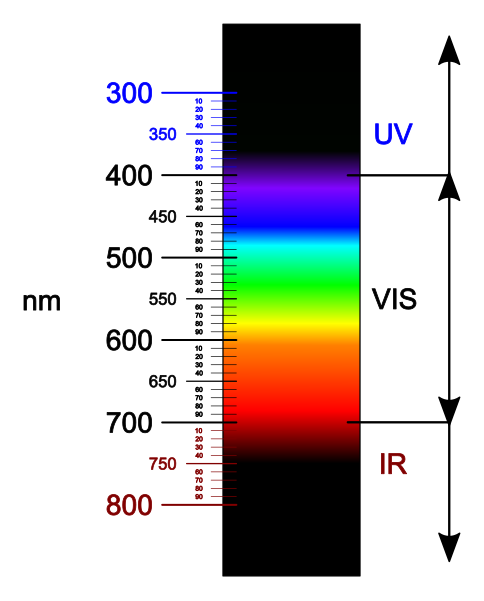

Engelmann presents the example of teaching students the color “blue.” The last thing you want to do is have them memorize a definition; a student who can recite that “blue is the hue of that portion of the visible spectrum lying between green and indigo, evoked in the human observer by radiant energy with wavelengths of approximately 420 to 490 nanometers” won’t be very successful in actually picking blue out of a ROYGBIV line up. Instead, students need to be shown many examples of blue things, all varying in every respect except color, and also, just as crucially but often neglected, many non-examples of blue. Most efficiently, those will be examples of not-blue that are closest to blue without being blue. “If we show the difference between blue and green,” Englemann writes, “yellow is automatically not blue because it is less like blue than green is.” A student who calls purple “blue” can only do so because he has encountered ambiguous examples, an easily solvable design problem rather than a thorny puzzle of human psychology.

Once the curriculum has been designed and tested, the teacher - who, again, Engelmann emphatically separates from the curriculum designer - is given a script for presenting the material and left with the task of applying behaviorist techniques to drill the students. Engelmann’s curricula specify exactly how often students must produce a correct response on the first try to consider a given bit of information or specific procedure mastered; only then is the foundation set to layer on more advanced material. He also sets a ratio for how much new material and review each lesson should contain: about a 10/90 split. Engelmann found that the typical student requires far more practice to reach mastery than is included in most educational programs, a finding I have replicated in my own homeschool.

To Engelmann’s credit, he seems to realize he only has hold of the elephant’s tail and the tail of an elephant raised in captivity at that. He states up front that he will not treat (or rely upon) “variables that lie outside those the teacher can control,” such as what an individual student might find interesting or motivating. Still, he promises a fool-proof method for teaching Dumbo some circus tricks and concludes that “the program is at fault if observations reveal that students fail.”7 I share Engelmann’s belief that all children can learn and admire his deep sense of teachers’ responsibility to their students - all of their students, regardless of background or innate ability:

The major difference between higher and lower performers is the rate at which they learn the material, not the way they formulate inferences… This difference does not support designing one sequence for higher performers and another for lower performers, but rather providing more repetition and practice for the lower performers.

While they have lately been rediscovered and given new names by cognitive science,8 the principles that are at work here are quite old. My favorite Jesuit pedagogue often advises teachers to “give a minimum of precept, a maximum of practice” and to teach from examples rather than rules and definitions. Lengthy drill was a technique used along side the switch in the bad old days; repetitio est mater studiorum, as Fr. Donnelly would have said. Though Engelmann, like the cognitive science of learning folks, seems to have no sense of himself as working in any pedagogical tradition, his work can be seen as an attempt to systematize the application of these principles through “logico-empirical analysis,” and it seems to work well for at least some definitions of work well.

But what if exclusively pursuing outcomes the teacher can control undermines other, more elusive educational goals we might have, ones that we can only work toward indirectly? What happens when Dumbo graduates? Does it matter that we all hate using 100 Easy Lessons?

“Well, for goodness’ sakes!” said Aunt Abigail. She turned and called across the the room, “Henry, did you ever! Here’s Betsy saying she don’t know what we make butter out of! She actually never saw anybody making butter!”

Uncle Henry was sitting down, near the window, turning the handle to a small barrel swung between two uprights. He stopped for moment and considered Aunt Abigail’s remark… Then he began to turn the churn over and over again and said, peaceably: “Well, Mother, you never saw anybody laying asphalt pavement, I’ll warrant you! And I suppose Betsy knows all about that.

Elizabeth Ann’s spirits rose. She felt very superior indeed. “Oh, yes,” she assured them, “I know all about that! Why, I’ve seen them hundreds of times! Every day as we went to school they were doing the whole pavement for blocks along there.”

Aunt Abigail and Uncle Henry looked at her with interest, and Aunt Abigail said: “Well, now, think of that! Tell us all about it!”

“Why, there’s a big black sort of wagon,” began Elizabeth Ann, “and they run it up and down and pour out the black stuff on the road. And that’s all there is to it.” She stopped, rather abruptly, looking uneasy. Uncle Henry inquired: “Now there’s one thing I’ve always wanted to know. How do they keep that stuff from hardening on them? How do they keep it hot?”

The little girl looked blank. “Why, a fire, I suppose,” she faltered, searching her memory desperately and finding there only a dim recollection of a red glow somewhere connected with the familiar scene at which she had so often looked with unseeing eyes.

“Of course a fire,” agreed Uncle Henry. “But what do they burn in it, coke or coal or wood or charcoal? And how do they get any draft to keep it going?”

Elizabeth Ann shook her head. “I never noticed,” she said.

Aunt Abigail asked her now, “What do they do to the road before they pour it on?”

“Do?” said Elizabeth Ann. “I didn’t know they did anything.”

“Well, they can’t pour it right on a dirt road, can they?” asked Aunt Abigail. “Don’t they put down cracked stone or something?”

Elizabeth Ann looked down at her toes. “I never noticed,” she said.

“I wonder how long it takes for it to harden? said Uncle Henry.

“I never noticed,” said Elizabeth Ann, in a small voice.9

Englemann’s insights are real and really useful. Anything we require a student to learn, it seems only fair to teach them in as efficient and effective a way as possible. And yet, if Engelmann’s approach avoids many pitfalls, it also minimizes potential aids to the educator’s task - interest and curiosity among them - but perhaps more fatally, if relied on exclusively, if taken for the whole elephant, it undermines the development of other intellectual virtues besides docility.

“For modern youngsters there is no tedious climbing of the hill of knowledge, for an escalator takes them from kindergarten to high school graduation without their ever knowing the joy of honest, sustained effort,” Ella Frances Lynch warned a century ago. What happens to students who are spoon fed their education? For whom all knowledge comes carefully pre-measured, prepared, even predigested? They remain forever intellectually children, at the mercy of whoever is willing to teach them - to whatever end. They are doomed to a life of intellectual dependence, slurping education - in a cup!

Some links!

For more on this pedagogical problem from a slightly different, more ancient angle, see John Psmith’s review of The Education of Cyrus.

Nadya Williams on the necessity of a family library.

Dixie’s piece on imagining history through sound was really neat - we’ve done a fair bit of listening to music from historical periods we’ve studied, but she goes beyond that.

Audrey Watters, author of Teaching Machines: The History of Personalized Learning, is back writing on ed tech again, and I am excited.

Dan Meyer often writes about how ed tech founders on this, the challenge of the 95%.

Educational progressives will be happy to know that the Angelic Doctor acknowledges you can also acquire knowledge by discovery, but you’re going to need the habit of shrewdness.

I’m particularly partial to John Godfrey Saxe’s verse rendition.

If you spent any time around Substack this week, you probably encountered this very characteristic example of educational progressivism.

Why should homeschoolers be interested in a method mainly directed at efficiently schooling public school classrooms full of children? Well, he also happens to be the guy behind possibly the most popular resource homeschoolers hate to use, How to Teach your Child To Read in 100 Easy Lessons.

This is where John Stuart Mill comes in, as Engelmann thinks his System of Logic provides perfect guidance for this project.

The main causes of failure are including inferential jumps that are too large or requiring too few repetitions.

Overlearning! Interleaving! Retrieval practice! Deliberate practice!

Homeschooling mother, if you have not yet read Understood Betsy, I am begging you to do so ASAP - it makes a wonderful read aloud, too!

Watching my 3 children learn to read, using 100 Easy Lessons, is one of the delights of my life.

I earned a teacher certification in 2001. We were only taught how to teach whole language nonsense. As soon as I had my first classroom, I saw that method fail my students. I purchased Hooked On Phonics. .

My mom friend uses the public school version of 100 Easy Lessons to teach her child with Down Syndrome. She said in their community it’s well-known to be the program that works.

There is a second book called Funnix (it comes with an unpleasant computer program by the same authors for the second hundred lessons. My 17 year old remembers the silly and fun stories from both the 1st 100 and 2nd 100 lessons.

My 7 year old is now reading Misty of Chincoteague.

I love 100 Easy Lessons. Can’t wait to teach my grandkids with it.

Truly enjoyed this article. I'm learning so much about the Catholic educational tradition -- pardon me if my inference is incorrect here though.

One note: I understand the criticism of progressive and traditionalist K12. I've written extensively about it on my own Substack being a PTSD-ridden ex-conventional high school teacher.

Now, in my classical charter school (still public, still run under the state's purview so very difficult to thread the needle on what classical probably should look like) all I can say is this:

I was the exception in the conventional public school system. Students loved learning in my classroom (mostly the humanities) and I was fiercely demanding. The issue, as always, is scale -- something homeschoolers wisely recognize and escape. I think the classical tradition gives us the best roadmap for how to effect deeper learning -- but you still have all the problems with scaling for students of incredible variation in skill, knowledge, and support at home. This is what makes teaching impossible, but also incredibly fun for the masochists in our world.

For all your readers, know that I truly believe all parents can and should homeschool, if only because of comparative advantage given how far the conventional public schools have fallen n terms of ability to actually teach -- largely due to pants-on-head stupid policy from educational "leadership" at the university level. I'm glad I found your substack; it's thoughtful and gives me a touchstone for my practice.

Also, you're hilarious. Thanks for the lift this morning.